Should I Start Smoking Again Vaping

- Enquiry

- Open Access

- Published:

Associations between vaping and relapse to smoking: preliminary findings from a longitudinal survey in the UK

Harm Reduction Journal volume 16, Article number:76 (2019) Cite this article

Abstruse

Groundwork

Most smokers attempting to quit relapse. There is little show whether the use of e-cigarettes ('vaping') increases or decreases relapse. This study aimed to assess ane) whether vaping predicted relapse among ex-smokers, and 2) amidst ex-smokers who vaped, whether vaping characteristics predicted relapse.

Methods

Longitudinal spider web-based survey of smokers, recent ex-smokers and vapers in the UK, baseline in May/June 2016 (due north = 3334), follow-upwardly in September 2017 (n = 1720). Those abstinent from smoking ≥ 2 months at baseline and followed up were included. Aim 1: Relapse during follow-up was regressed onto baseline vaping status, age, gender, income, nicotine replacement therapy utilize and time quit smoking (n = 374). Aim 2: Relapse was regressed onto baseline vaping frequency, device type, nicotine strength and time quit smoking (n = 159).

Results

Overall, 39.vi% relapsed. Compared with never utilize (35.ix%), past/ever (45.9%; adjOR = 1.13; 95% CI, 0.61–2.07) and daily vaping (34.v%; adjOR = 0.61; 95% CI, 0.61–ane.89) had similar odds of relapse, for non-daily vaping evidence of increased relapse was inconclusive (65.0%; adjOR = 2.45; 95% CI, 0.85–7.08). Amidst vapers, not-daily vaping was associated with higher relapse than daily vaping (adjOR = iii.88; 95% CI, one.ten–xiii.62). Compared with modular devices (18.9% relapse), tank models (45.6%; adjOR = iii.63; 95% CI, ane.33–9.95) were associated with increased relapse; evidence was unclear for disposable/cartridge refillable devices (41.9%; adjOR = 2.83; 95% CI, 0.90–8.95). Nicotine forcefulness had no clear association with relapse.

Determination

Relapse to smoking is likely to exist more common among ex-smokers vaping infrequently or using less advanced devices. Research into the effects of vaping on relapse needs to consider vaping characteristics.

Introduction

Smoking remains the primary preventable crusade of affliction and premature expiry in countries with a high socio-demographic index such as the Uk (United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland) [i]. Population surveys from the USA, Great britain, Canada and Australia show that at least a third of smokers take made a serious attempt to quit smoking in the past year [2, 3].

However, the vast majority of attempts are non successful. In unaided attempts, less than v% are still abstemious 1 year after they made a quit endeavor [four]. A recent review and modelling written report showed that after 12 weeks of licenced pharmacotherapy, abstinence rates at one twelvemonth were 23% for varenicline, the most effective handling, 17% for bupropion, thirteen% for nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and viii% for placebo. Forbearance rates drop most steeply in the kickoff week, and later about a month, the rate of returning to smoking slows down considerably [5]. A return to smoking after an initial period of forbearance is by and large defined as relapse, simply there is no agreed definition of the length of the menstruation of abstinence [vi]. Interventions could reduce relapse by preventing initial cursory lapses, preventing lapses from leading to full relapse or both [six]. Even so, in that location is petty testify on effective interventions to reduce relapse with evidence of a do good available only for varenicline [half dozen].

In addition to the licenced pharmacotherapies, e-cigarettes have become available as a quitting aid and since 2013, due east-cigarette use (vaping) has been the most mutual form of support in attempts to quit smoking in England [7, viii]. Longitudinal studies assessing vaping and smoking abeyance indicate that frequency of use and type of device used are important; daily use, in particular daily utilise of more than advanced devices, has been associated with quitting behaviour and abstinence from smoking [nine,x,11].

While many studies accept looked at vaping and its effects on smoking cessation [8], to date, very trivial testify is bachelor on its effect on relapse. A recent analysis of a longitudinal U.s. survey [12] found that former smokers who vaped daily or non-daily had a greater risk of relapse compared with never vapers. Withal, there was no minimum length of abstinence to be categorised equally a former smoker and the study did non adjust for any vaping characteristics. A second written report using the same survey separated out smokers who had quit for less or more 12 months and assessed relapse associated with different frequencies of vaping [13]. In contempo ex-smokers, vaping was not significantly associated with relapse at follow-up; in longer-term ex-smokers, prior vaping and electric current regular vaping were associated with higher relapse [13]. A recent qualitative study in the United kingdom concluded that smoking lapses were perceived differently when e-cigarettes were used, with lapses seen equally permissible [14]. The authors' analysis of the feel of vapers quitting smoking suggests that vaping could support long-term relapse prevention. This is besides supported by a recent randomised controlled trial showing college abstinence and higher usage for e-cigarettes than for nicotine replacement therapy at 1-year follow-upward [fifteen].

In the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, vaping has been increasing among longer-term ex-smokers [xvi, 17] and many vapers use east-cigarettes for a prolonged period of time, with one-third of current users in Great U.k. having vaped for more than than 2 years [8]. If vaping protected against relapse, increased use and longer-term utilise among ex-smokers would have a positive effect on public health. If even so vaping among ex-smokers increased the risk of relapse, the increased uptake and prolonged apply would have an overall negative result.

The aims of this written report were to assess in a sample of ex-smokers whether:

- 1.

Vaping was associated with subsequent relapse to smoking when adjusting for demographics, electric current employ of other nicotine and time since they quit smoking.

- 2.

Amid those who vaped, characteristics of vaping (frequency, device type, nicotine forcefulness) were associated with subsequent relapse to smoking.

Methods

Study design and sample

This study used data from a longitudinal web-based survey of a national general population sample of smokers, ex-smokers and vapers aged 18 and over in the U.k.. Participants were recruited through Ipsos MORI, a leading market inquiry organisation in the UK, from members of an online panel managed past Ipsos Interactive Services. At recruitment, quotas were imposed on demographics to include a representative sample of age, sex and geographical region. Console members were invited via email to take part in the survey. To reduce bias, the electronic mail did not specify the topic of the survey. Console members received points for completing surveys which were redeemable for shopping vouchers. Participants were asked to give consent electronically prior to commencing the survey and were screened for smoking status with only smokers and ex-smokers being eligible to take part. The questionnaires took an estimated 15 to 20 min to complete.

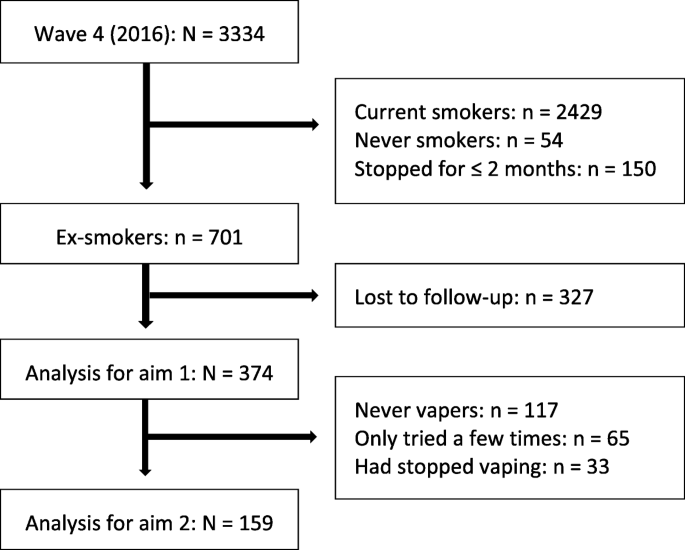

There have been v waves of the survey: wave ane in November/December 2012 (North = 5000), wave 2 in December 2013 (follow-up, N = 2182), and moving ridge 3 in December 2014 (follow-up, N = 1519). At wave 1, all participants were smokers or recent ex-smokers, i.due east. had smoked inside the previous 12 months. Wave four was conducted in May/June 2016 (N = 3334); 933 participants were followed up from the previous three waves and an boosted 2403 smokers, recent ex-smokers or exclusive vapers recruited. Wave v was completed in September 2017 (North = 1720) with 602 who were involved in all waves and the remainder followed up from wave 4. The nowadays analyses only focused on data from wave 4 in 2016 and wave 5 in 2017; additional details about these are provided elsewhere [eighteen, nineteen]. For both aims, just those who had quit smoking for more than 2 months at wave iv and were successfully followed upwards at wave v were included in the assay (n = 374, Fig. ane). For aim 2, the sample was further restricted to ex-smokers who vaped at moving ridge 4 (due north = 159, Fig. i).

Flowchart of inclusion and exclusion of participants

Measures

All variables included in the analyses were collected at wave four except for the event variable which used data from wave 5.

Socio-demographic information included historic period in years (continuous). Gender was recorded as male and female. For annual income, respondents selected ane response option (under £6500, £6500–£xv,000, £15,001–£30,000, £30,001–£twoscore,000, £40,001–£l,000, £fifty,001–65,000, £65,001–£95,000, £95,001 and over, 'don't know/prefer non to say'). The UK government defined 'low income' every bit below 60% of the national median, which in 2016/2017 equated to nearly £15,400 [20]. Therefore, responses were collapsed into 'upwards to £15,000' (low income), '£15,001 to £thirty,000' (middle income) and 'over £30,000' (loftier income). Those who selected 'don't know/prefer non to say' were retained every bit 'not disclosed'. Ethnicity was recorded using Britain census categories [21]. It was not included in the assay considering white English/Welsh/Scottish/Northern Irish gaelic/British was selected by ninety.9% (n = 340) and all other categories by fewer than 10 participants (Additional file 1: Table S2). To avoid small groups, categories would have to be collapsed so much as to have little informative value.

Smoking status, fourth dimension since quit smoking, vaping characteristics and NRT use were assessed using questions and response options detailed in Tabular array 1.

The outcome variable was a binary categorisation of relapse to smoking, derived from smoking condition at waves 4 and v. Those identified as ex-smokers at wave 4 who gave a response at moving ridge v other than 'I stopped smoking completely before the last survey [wave iv]' were categorised as having relapsed. This definition of relapse included those who were abstinent at follow-upward only had lapses or relapsed to smoking in between waves.

Assay

Attrition analysis was conducted for all ex-smokers at moving ridge 4; chi-square statistics were used to compare follow-upwardly rates by time quit smoking, vaping status, gender, income and NRT use. Hateful age for those followed up and lost to follow-up was compared using an contained groups t examination.

-

Aim 1: Relapse rates were calculated overall and by respondent feature. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the association between relapse, vaping status (daily employ, non-daily use, past/ever use compared with never use), gender, age, income, NRT utilize and time quit smoking.

-

Aim 2: Relapse rates were calculated in this sample overall and by respondent characteristics. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression was used to appraise the association between relapse, frequency of eastward-cigarette use (non-daily compared with daily employ), type of electronic cigarette used most, nicotine strength used nigh and time quit smoking. Bivariate analyses were also conducted to assess the associations between gender, age, income and NRT employ, but because of the small sample size, the multivariable analysis did not adjust for these variables. Postal service-hoc sensitivity analyses were run without those (n = fifteen) who did non know the force of nicotine they used and using four categories (no nicotine, 1 to 8 mg/ml, 9 to 14 mg/ml, xv mg/ml and over).

In add-on to the logistic regressions, Bayes factors were calculated for the association between vaping condition and relapse to smoking for both aims. Bayes factors are the ratio of the (average) likelihood of two hypotheses being correct given a set of data. The two hypotheses are typically that an intervention had a desired result ('H1 hypothesis') versus that it had no effect ('null hypothesis') [22]. Bayes factors are particularly useful for the evaluation of non-significant effects as they tin indicate if there is support for either of the hypotheses or if the data are insensitive (e.grand. due to small sample sizes). A Bayes cistron of more than 3 can be taken as evidence against the nothing hypothesis and anything beneath 0.three can be considered evidence for the nada hypothesis. A Bayes factor between 0.3 and 3 is considered to point insensitive data [22]. This means that findings with p values greater than the commonly used 0.05 cut-off should only be presented equally 'lack of association' if the Bayes factor is < 0.3 [22]. Calculation of Bayes factors requires specification of an expected effect size based on previous research. For the nowadays calculation, the expected effect size was based on past research looking at relapse for other NRT users [23]. Using Dienes' Bayes factor calculator [24], the mean was set at 0, the tails fix to ii and the logarithm of the odds ratio used for the sample mean.

Results

Attrition and sample characteristics

While follow-upward rates were low from wave 4 to wave 5 (51.vi%), follow-upward for ex-smokers at moving ridge four showed very little variation past time since they had quit smoking, vaping status, NRT use, gender or income; only age differed between groups with those followed upwardly on average older than those lost to follow-up (Additional file one: Table S1 for details).

Sample characteristics are presented for the two analyses in Table 2. Of all ex-smokers, 37.four% had stopped between ii and 12 months earlier moving ridge 4 and 62.vi% over 12 months before moving ridge 4; 42.5% were vaping, 26.2% had only tried a few times or had stopped vaping and 31.three% had never tried vaping at moving ridge 4. In both samples (all ex-smokers and vaping ex-smokers), in that location were slightly more men than women, over two-thirds were aged between xl and 54, around four in ten had a high income and just over 1 in 10 were using NRT. Amidst those who vaped, most vaped daily and nigh half used tank models; 11.3% used no nicotine, ix.4% did not know the nicotine content, 45.9% used 1 to 14 mg/ml and 33.3% used nicotine concentrations higher up xv mg/ml (Table ii).

Aim one: Association between vaping status and subsequent relapse to smoking

Overall, 39.6% of ex-smokers who had stopped for at least ii months at wave four relapsed to smoking during the follow-up flow. Compared with those who had never vaped (35.9% relapse), those who vaped non-daily had higher rates of relapse (65.0%, Bayes gene 1.01), although this association was weakened and no longer significant when adjusting for covariates (adjusted OR = ii.45; 95% CI, 0.85 to seven.08; p = 0.098; Table 3). Past/ever users (45.ix%; Bayes factor 0.99; adjusted OR = 1.xiii; 95% CI, 0.61 to 2.07; p = 0.070) and daily users (34.five%; Bayes gene 0.99; adjusted OR = 1.07; 95% CI, 0.61 to one.89; p = 0.80; Table 3) had relapse rates closer to those of never users. Fourth dimension quit smoking was strongly associated with relapse with more recent ex-smokers more likely to relapse. Higher age was associated with reduced relapse. In unadjusted results, those using NRT were more probable to relapse. At that place was little divergence past gender or income (Tabular array 3). Relapse rates for respondent characteristics for all response options individually (where these were collapsed in the regressions) are provided in Additional file 1: Tabular array S3.

Aim 2: Association between vaping characteristics and subsequent relapse to smoking

Amid the smaller sample of ex-smokers who were vapers at wave 4, 38.four% relapsed. Non-daily use was associated with college rates of relapse than daily utilize (65.0% versus 34.5%; Bayes factor 1.01; adjusted OR = 3.88; 95% CI, one.10 to 13.62; p = 0.035; Tabular array four). Compared with vapers using modular devices (eighteen.9%), those using whatsoever other device had higher rates of relapse. For those using disposable or cartridge refillable devices, this clan with higher relapse was adulterate when adjusting for other characteristics (41.9%; adjusted OR = two.83; 95% CI, 0.90 to eight.95; p = 0.076; Table 4); for tank models, the association remained meaning (45.half-dozen%; adjusted OR = 3.63; 95% CI, one.33 to 9.95; p = 0.012; Table iv). Nicotine strength had no clear association with relapse (compared with 15 mg/ml and over: one to 14 mg/ml: adjusted OR = i.51; 95% CI, 0.66 to three.44; p = 0.33; no nicotine or unknown nicotine strength: adjusted OR = 0.54; 95% CI, 0.17 to 1.74; p = 0.30; Tabular array 4). The postal service-hoc sensitivity analysis indicated fiddling alter in relapse rates for the remaining 'no nicotine' group (38.9% relapse versus 36.four% when combined with 'unknown') and like relapse rates across the ii categories that were combined in the master assay (i to viii mg/ml, 44.seven% relapse; 9 to xiv mg/ml, 45.7% relapse). As before, shorter time since quit smoking was strongly associated with relapse (Table 4). Relapse rates for respondent characteristics without collapsing response options are provided in Additional file 1: Table S3.

Discussion

In a group of ex-smokers who had stopped for at to the lowest degree 2 months, those who used e-cigarettes infrequently at baseline were somewhat more likely to relapse to smoking over the post-obit 15-calendar month period than those who had never used e-cigarettes, whereas those who used e-cigarettes daily were just equally likely to relapse as never users. When merely examining vapers at baseline, non-daily users were more probable to relapse than daily users. Those using devices other than modular devices as well appeared to be more probable to relapse to smoking whereas there was picayune association between nicotine strength used and relapse.

Exceptional vaping was associated with college relapse to smoking in vapers. Vaping and also use of NRT may exist a marking of higher dependence on nicotine which is consistently associated with increased relapse [25]. This is supported past evidence that vapers were more probable than non-vapers to report higher cigarette dependence when they were smoking [26]. Infrequent apply and thus nicotine consumption would not sufficiently protect confronting this increased risk of relapse. Moving from identifying every bit a smoker to identifying oneself as an ex-smoker is likewise of import in maintaining long-term abstinence [27] and information technology could be speculated that exceptional vapers have not fully switched to a new identity [28]. Vaping can besides increase exposure to smoking-related cues, particularly if vapers use designated cigarette smoking areas.

Nicotine strength was not associated with relapse; this may partly be because the amount of nicotine available to the user is non solely determined by the concentration of nicotine in the liquid but besides by the corporeality of liquid consumed, user characteristics such as puffing patterns, and the device blazon and device settings used [29,30,31,32]. In addition, the small-scale sample in this analysis made information technology difficult to observe an consequence, and the grouping of strengths may take masked smaller effects, although this was not apparent in the sensitivity analysis which used more precise groupings. We categorised according to the strength used about ofttimes merely merely a small grouping of users (n = 12) used more than one strength.

There are a few limitations that demand to be considered when interpreting the findings. Firstly, there was a large attrition rate between waves 4 and 5. However, follow-up rates for ex-smokers and for ex-smokers who vaped were very like to the overall sample suggesting that findings would have been similar with higher follow-up rates. The small sample sizes bachelor in this report may have failed to detect statistically meaning furnishings due to depression power. It was not possible to include information on smoking dependence prior to quitting or motivation to remain quit from smoking, variables that affect the chances of abstinence. Categories for variables were wide and more fine-grained information on vaping characteristics may accept provided further insight.

The calculated Bayes factors for vaping were close to 1 for all categories, indicating that the information are insensitive rather than evidence for a lack of clan [33]. Equally there was a lack of previous research looking at e-cigarettes and relapse, the effect size for the adding was based on past enquiry looking at relapse for NRT users [23] and may not directly employ to this research. All information were self-reported, which may result in recall or social desirability bias and did not allow for biochemical verification of abstinence. However, previous prove indicates that levels of misreporting of abstinence in surveys are low [34]. There are likely to be additional confounding factors not accounted for in the present study which may bear upon the association between characteristics and relapse. For example, other studies found that vapers had been more than dependent smokers [26] and that in full general, tardily relapse to smoking was predicted by cocky-efficacy and dependence [35, 36], factors we were unable to include in this analysis. Finally, equally this is an observational study, we cannot assign causality to the observed associations.

A strength of this study is that the sample came from a general population survey. It is also 1 of the kickoff studies to expect at vaping and relapse to smoking and the offset to explore associations between device type and nicotine content. It is worth noting that this analysis included ex-smokers regardless of the type of support they had initially used when quitting smoking.

Findings for relapse in the nowadays analysis are in line with previous inquiry for smoking cessation showing differences in the likelihood of quitting smoking by blazon of device and frequency of utilize; where compared with not-e-cigarette users, non-daily cigalike (dispensable/pre-filled) users were less likely to quit [xi]. More advanced devices are likely to be more efficient at delivering nicotine and offer a longer battery life [37]. Notwithstanding the link between nicotine delivery and abstinence, qualitative testify suggests individuals may create a bespoke successful arroyo to suit their needs [28]. Analyses of U.s. survey data from 2013 to 2015 found that non-daily due east-cigarette users had a greater risk of smoking relapse compared with never users [12], which, when separating out contempo and longer-term ex-smokers, remained true for non-regular use among recent ex-smokers [thirteen]. Even so, unlike the present study, those analyses also plant increased relapse for daily use overall and for regular utilise amongst longer-term ex-smokers. The grouping of longer-term ex-smokers likely included old smokers of decades whereas in the present study, no one had stopped earlier 2012 and most had stopped within the by two years, thus making the sample more than similar to the recent ex-smokers in the US information. The years of data collection are likely to be relevant for associations betwixt vaping and smoking behaviour as devices are evolving constantly. Additionally, vaping and smoking statuses were assessed differently in the unlike surveys and the present report used a stricter criterion of relapse. Similar to findings from smoking abeyance [38,39,40], older participants were more likely to remain abstinent from smoking.

Hereafter inquiry looking at associations betwixt vaping and relapse to smoking needs to include information on the duration of cessation, prior smoking characteristics (such every bit dependence) and more than detailed information on characteristics of vaping such every bit frequency (ideally beyond a binary measure of daily/non-daily), device blazon and nicotine content. Interactions between these variables should exist considered; there are for instance likely to be interactions between type of device and frequency of use every bit well equally betwixt blazon of device and nicotine strength. The role of dependence and motivation to remain abstinent from smoking should be examined in sufficiently large samples.

Conclusion

In a group of ex-smokers who had stopped smoking for at least ii months, relapse to smoking during a 15-month follow-up flow was probable to be more common among those who at baseline vaped infrequently or used less advanced devices. Research into the effects of vaping on relapse to smoking needs to consider characteristics of use including devices used and frequency of use.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during the electric current report are available from the corresponding writer on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- NRT:

-

Nicotine replacement therapy

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

References

-

Tobacco Collaborators GBD. Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Affliction Study 2015. Lancet. 2017;389(10082):1885–906.

-

Borland R, Partos TR, Yong HH, Cummings KM, Hyland A. How much unsuccessful quitting action is going on among adult smokers? Information from the International Tobacco Control Four Country cohort survey. Addiction. 2012;107(3):673–82.

-

Beard E, West R, Michie S, Brownish J. Association between electronic cigarette use and changes in quit attempts, success of quit attempts, use of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy, and use of stop smoking services in England: time serial analysis of population trends. BMJ. 2016;354:i4645.

-

Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence amongst untreated smokers. Addiction. 2004;99(1):29–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.360-0443.2004.00540.10.

-

Jackson SE, McGowan JA, Ubhi HK, Proudfoot H, Shahab L, Brown J, et al. Modelling continuous abstinence rates over fourth dimension from clinical trials of pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation. Habit. 2019;114(five):787-97.

-

Livingstone-Banks J, Norris E, Hartmann-Boyce J, Westward R, Jarvis M, Hajek P. Relapse prevention interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2:CD003999.

-

Brown J, West R, Beard Eastward. Smoking Toolkit Study. Trends in electronic cigarette employ in England. http://wwwsmokinginenglandinfo/latest-statistics/. 2018.

-

McNeill A, Brose LS, Calder R, Bauld L, Robson D. Show review of eastward-cigarettes and heated tobacco products 2018. A report commissioned past Public Health England. London: Public Health England; 2018. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/east-cigarettes-and-heated-tobacco-products-evidence-review

-

Biener Fifty, Hargraves JL. A longitudinal study of electronic cigarette use among a population-based sample of adult smokers: association with smoking cessation and motivation to quit. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(2):127–33.

-

Brose LS, Hitchman SC, Dark-brown J, West R, McNeill A. Is the use of electronic cigarettes while smoking associated with smoking cessation attempts, cessation and reduced cigarette consumption? A survey with a ane-twelvemonth follow-up. Habit. 2015;110(7):1160–8.

-

Hitchman SC, Brose LS, Dark-brown J, Robson D, McNeill A. Associations betwixt e-cigarette blazon, frequency of use, and quitting smoking: findings from a longitudinal online panel survey in Great Britain. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(10):1187–94.

-

Verplaetse TL, Moore KE, Pittman BP, Roberts West, Oberleitner LM, Peltier MR, et al. Intersection of e-cigarette employ and gender on transitions in cigarette smoking status: findings across waves 1 and 2 of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(x):1423-8.

-

Dai H, Leventhal AM. Association of electronic cigarette vaping and subsequent smoking relapse amongst former smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;199:10–7.

-

Notley C, Ward E, Dawkins L, The netherlands R, Jakes S. Vaping as an culling to smoking relapse following brief lapse. Drug Booze Rev. 2019;38(1):68–75.

-

Hajek P, Phillips-Waller A, Przulj D, Pesola F, Myers Smith K, Bisal Due north, et al. A randomized trial of eastward-cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement Therapy. North Engl J Med. 2019;380(7):629-37.

-

Kock L, Shahab 50, West R, Brown J. E-cigarette use in England 2014-17 as a role of socio-economic profile. Addiction. 2018;114(2):294-303.

-

McNeill A, Brose LS, Calder R, Bauld L, Robson D. Vaping in England: an evidence update February 2019. A report deputed past Public Wellness England. London: Public Health England; 2019.

-

Lee HS, Wilson S, Partos T, McNeill A, Brose LS. Awareness of changes in e-cigarette regulations and behaviour before and after implementation: a longitudinal survey of smokers, ex-smokers and vapers in the U.k.. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019. Epub ahead of print.

-

Wilson S, Partos T, McNeill A, Brose LS. Harm perceptions of east-cigarettes and other nicotine products in a Great britain sample. Addiction. 2019;114(5):879-88.

-

Department for Piece of work & Pensions. Households below average income: 1994/95 to 2016/17: an assay of the UK income distribution: 1994/95-2016/17. London: Crown copyright; 2018.

-

Role for National Statistics. 2011 Census Variable and Classification Information2014 6 Sept 2017.

-

Beard E, Dienes Z, Muirhead C, W R. Using Bayes factors for testing hypotheses about intervention effectiveness in addictions research. Addiction. 2016;111(12):2230-47.

-

Hajek P, Stead LF, West R, Jarvis Grand, Hartmann-Boyce J, Lancaster T. Relapse prevention interventions for smoking abeyance. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;8:CD003999.

-

Dienes Z. Bayes Factor calculator. http://www.lifesci.sussex.ac.uk/home/Zoltan_Dienes/inference/bayes_factor.swf. Accessed 16 Oct 2019.

-

Vangeli E, Stapleton J, Smit ES, Borland R, West R. Predictors of attempts to stop smoking and their success in adult general population samples: a systematic review. Addiction. 2011;106(12):2110–21.

-

McNeill A, Driezen P, Hitchman SC, Cummings KM, Fong GT, Borland R. Indicators of cigarette smoking dependence and relapse in former smokers who vape compared with those who do not: findings from the 2016 International Tobacco Control Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey. Habit. 2019;114(Suppl 1):49–60.

-

Tombor I, Shahab L, Brown J, Notley C, West R. Does non-smoker identity following quitting predict long-term forbearance? Testify from a population survey in England. Addictive Behav. 2015;45:99–103.

-

Notley C, Ward E, Dawkins 50, The netherlands R. The unique contribution of eastward-cigarettes for tobacco harm reduction in supporting smoking relapse prevention. Harm Reduct J. 2018;15(one):31.

-

Talih Southward, Balhas Z, Eissenberg T, Salman R, Karaoghlanian N, El Hellani A, et al. Effects of user puff topography, device voltage, and liquid nicotine concentration on electronic cigarette nicotine yield: measurements and model predictions. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(2):150–7.

-

Hajek P, Przulj D, Phillips A, Anderson R, McRobbie H. Nicotine delivery to users from cigarettes and from different types of eastward-cigarettes. Psychopharmacology. 2017;234(5):773–9.

-

Dawkins L, Cox Southward, Goniewicz One thousand, McRobbie H, Kimber C, Doig M, et al. 'Real-world' compensatory behaviour with low nicotine concentration east-liquid: subjective furnishings and nicotine, acrolein and formaldehyde exposure. Addiction. 2018;113(10):1874–82.

-

Dawkins LE, Kimber CF, Doig Chiliad, Feyerabend C, Corcoran O. Self-titration by experienced e-cigarette users: blood nicotine delivery and subjective effects. Psychopharmacology. 2016;233(fifteen-16):2933–41.

-

Dienes Z. Using Bayes to get the virtually out of non-pregnant results. Front Psychol. 2014;5:781.

-

Wong SL, Shields One thousand, Leatherdale Southward, Malaison E, Hammond D. Cess of validity of self-reported smoking condition. Health reports. 2012;23(one):47–53.

-

Herd N, Borland R, Hyland A. Predictors of smoking relapse by duration of abstinence: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Addiction. 2009;104(12):2088–99.

-

Blevins CE, Farris SG, Brown RA, Stiff DR, Abrantes AM. The Function of self-efficacy, adaptive coping, and smoking urges in long-term cessation outcomes. Aficionado Disord Their Treat. 2016;fifteen(4):183–9.

-

Farsalinos KE, Spyrou A, Tsimopoulou M, Stefopoulos C, Romagna One thousand, Voudris V. Nicotine absorption from electronic cigarette use: comparison betwixt first and new-generation devices. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4133.

-

Brose LS, W R, McDermott MS, Fidler JA, Croghan E, McEwen A. What makes for an effective stop-smoking service? Thorax. 2011;66(ten):924–6.

-

Ferguson J, Bauld 50, Chesterman J, Approximate 1000. The English language smoking handling services: one-year outcomes. Addiction. 2005;100(Suppl 2):59–69.

-

Jackson SE, Kotz D, West R, Brown J. Moderators of real-world effectiveness of smoking abeyance aids: a population written report. Addiction. 2019;114(9):1627-38.

Acknowledgements

Nosotros give thanks all survey participants. Professor McNeill is a National Constitute for Health Research (NIHR) Senior Investigator. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and non necessarily those of the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Funding

This work was supported by Cancer Research UK (C52999/A21496; C57277/A23884).

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

All authors accept made substantial contributions to the conception of the work, the estimation of the information and substantially revised the work. LB and JB conducted the analysis and drafted the initial version of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Respective writer

Ethics declarations

Ideals approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for the survey was obtained from Male monarch's College London PNM Research Ethics panel. For waves 4 and 5, the codes are LRS15/162519 and LRS-16/17-4564.

Consent for publication

Non applicative.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher'south Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary data

Additional file 1: Tabular array S1.

Compunction rates for all wave 4 ex-smokers. Table S2. Ethnicity, northward=374. Table S3. Relapse by respondent characteristic showing all responses individually for variables where response options were combined for the main analysis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution four.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0/), which permits unrestricted employ, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided y'all give appropriate credit to the original author(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables license, and bespeak if changes were made. The Artistic Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Almost this article

Cite this article

Brose, 50.S., Bowen, J., McNeill, A. et al. Associations between vaping and relapse to smoking: preliminary findings from a longitudinal survey in the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland. Harm Reduct J 16, 76 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-019-0344-0

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12954-019-0344-0

wasingerclany1963.blogspot.com

Source: https://harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12954-019-0344-0

0 Response to "Should I Start Smoking Again Vaping"

Enregistrer un commentaire